As April and May approach, students across the UK face one of the most stressful periods of the year—exam season. Whether it’s GCSEs, A-levels, university exams, or other qualifications, the pressure to perform well can feel overwhelming. However, with the right strategies and mindset, students can navigate this challenging time effectively. This blog explores the common pressures of exam season and provides practical tips for managing stress and maintaining well-being.

Why Exam Pressure is High in 2025

Exam stress is not new, but in 2025, several factors may be amplifying it:

Common Signs of Exam Stress

Recognising stress early can help prevent burnout. Some common signs include:

Practical Strategies to Manage Exam Stress

To perform well while maintaining mental well-being, consider these effective strategies:

Advice for Parents & Teachers

Support from adults plays a crucial role in helping students manage exam pressure. Here’s how parents and teachers can help:

Final Thoughts

Exams are an important milestone, but they do not define a student’s future. By managing stress effectively and maintaining perspective, students can approach exams with confidence. If you or someone you know is struggling with exam pressure, don’t hesitate to reach out for help—whether it’s from a teacher, family member, or mental health professional.

Below are a few things you could try out in the classroom:

• Deliver activities to build resilience and manage anxiety

• Create safe spaces where pupils can go if they’re feeling overwhelmed

• Prepare students for the higher levels of anxiety or stress that they may feel in relation to exams and assessments

• Share coping and self-care strategies with students if you notice symptoms of stress

Stress is a powerful motivating force that is essential for healthy functioning. Problems really arise from the body and its crude mechanism for managing and understanding stress. You might remember plenty of times when you may have lost your temper or behaved somewhat erratically only to later realise that you were feeling stressed out; that is because stress is sneaky!

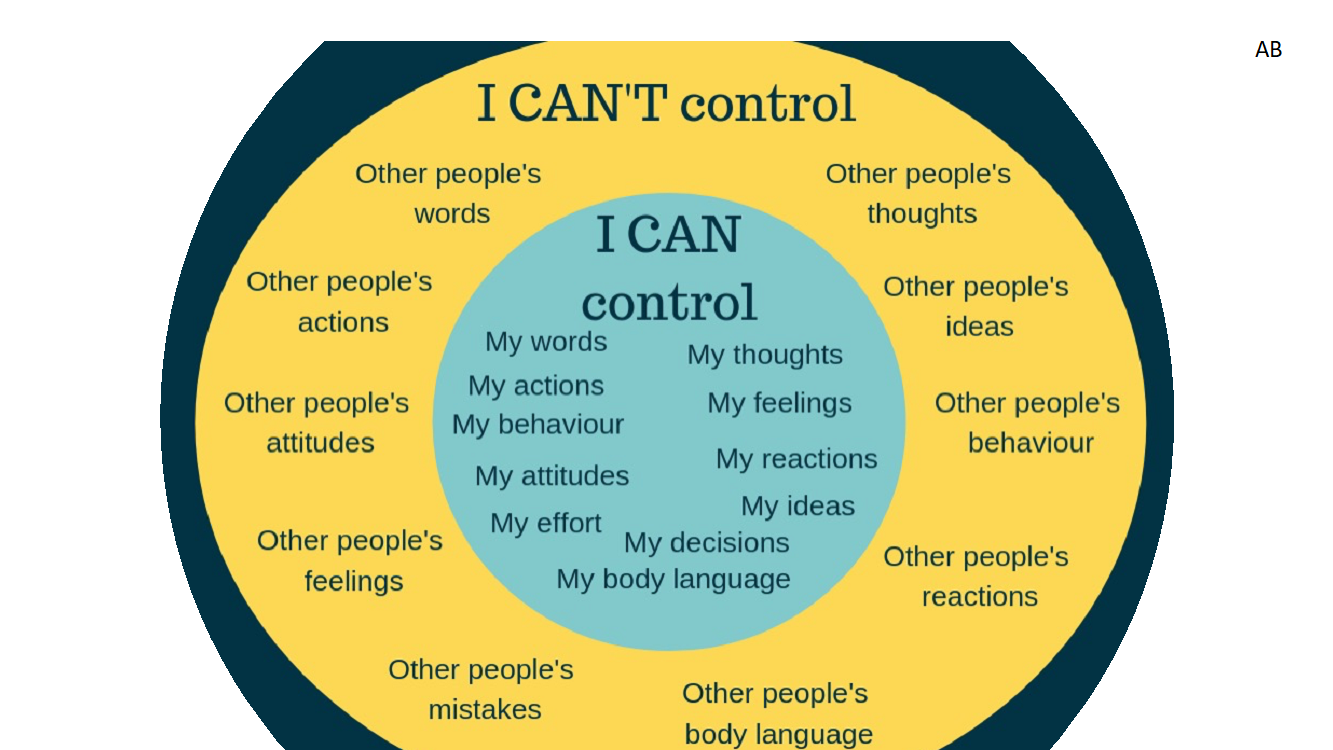

To manage these biological processes we often need to slow our bodies down and think strategically on how we use our resources to manage the challenges we face. In doing this, the first thing we need to consider is that not all stress can be managed alone. Sometimes things are just out of our control and it is important to think about what things we can control (e.g., how we approach a problem, making sure we have enough rest) and things we cannot control (e.g. organisational things which need to be communicated to others). If work is continually overburdening, then it will make little difference in the long run how we approach it and we need to look at this from an organisational level

Stress can also become somewhat addictive (e.g., rollercoasters, sky diving) and can also often come with rewards (e.g., feeling we have done a good job). What can at first glance appear as positive stress behaviours might become unhealthy if their continued cost to our wellbeing is not managed. These behaviours have been referred to as “badges of honour” and are typically things we do even though we know they are not good for us.

Have a think about what might be your badges of honour…

By paying attention to what we are saying to ourselves and what we are willing to putting our bodies through, we can start to see unhealthy patterns emerging; where unhelpful stress has begun locking in behaviours and sustaining itself (as mentioned before, stress is sneaky).

Ideally, we want to work within our window of tolerance which will be different for everyone. In this window, we are able to respond and react to stress and anxiety effectively (we have wiggle room). It is a comfort zone which allows us to self-soothe, self-regulate and be aware of our emotional state.

Try to think of a time when you were in a balanced, calm state of mind, when you felt relaxed and in control. Do you remember feeling calm, grounded, alert, safe and present? This is what it feels like when you are in this optimal zone.

When the balance is interfered with, either due to trauma or extreme stress, we end up leaving our window of tolerance. Our bodies typically react defensively to this and dysregulation occurs. When you start to deviate outside of your window of tolerance, you will start to feel agitated or anxious; you do not feel comfortable but you’re not out of control yet.

Past this point is where your body’s defence systems start to take over. You experience various symptoms such as anxiety and you are out of control. This is where our fight, flight, or freeze responses occur.

The prolonged result of this is a body that is out of balance and swinging from a state of hyperarousal (high energy) to a state of hypoarousal (low energy).

Hyperarousal is characterized by excessive activation or energy. You will usually experience a heightened sense of anxiety, which may make you more sensitive or overly responsive to things that occur in your daily life. Hyperarousal keeps your mind ‘stuck on’ and makes it difficult to eat/sleep/concentrate/manage emotions and in the extreme = rage and hostility.

Hypoarousal is the opposite. This experience of too little arousal is the result of freeze responses. Hypoarousal can also impact your sleep and eating habits, leaving you feeling emotionally flat. You will be unable to express yourself, process thoughts and emotions, and respond physically.

When experiencing the early stages of hyperarousal or hypoarousal you want to bring yourself back into the window of tolerance at this point. Beyond this point things get progressively difficult to control.

So what can we do to help us regulate ourselves more effectively?

There are some practical things we can do that work at a physical level within our bodies. If our body is experiencing hyperarousal we can try and counter this by providing our body opposite experiences to bring us back to a sense of equilibrium (and vice versa for hypoarousal).

Things that might decrease arousal

Things that might increase arousal

You may notice how many of these things are sensory; how we sense things and how “sensitive” we are is governed by how stressed we are feeling.

Alongside these physical techniques we can also use some cognitive techniques to think about thinking. This might sound obvious but as mentioned before stress is sneaky, it can embed itself in our bodies before we are even consciously aware. Thinking about thinking works by recognising what are the unhelpful thinking styles that often accompany dysregulation. When we recognise these styles we can then remind ourselves how irrational they are.

You’ll be amazed how often we slip into these thinking patterns. See if you recognise any from the list below:

By practicing both physical and cognitive stress management techniques we can build resilience to stress and increase our window of tolerance giving us more wiggle room and control over future stressful situations.

Whilst stress is unavoidable and sometimes out of our control there are nearly always things we can do to mitigate its impact. Being proactive in our own stress management is an important skill to master and key to supporting ourselves and others. Learning about what stress really is and pinning it down also equips us to relate and empathise with others that might be experiencing dysregulation.

As we mentioned at the start of this section, sometimes things are not operating on an individual level and we need look towards the environment around us. Looking at wellbeing at the organisational level is covered in the next section on whole school support.

( resources found)

How useful was this info?

Click on a star to rate it!

![]()

© Copyright Breathe 2020- 2024

Terms and Conditions | Privacy Policy

supporters & partners

![]()